Šejla Kamerić

- Works

- Exhibitions

- Fairs

- Editions/Books

-

News

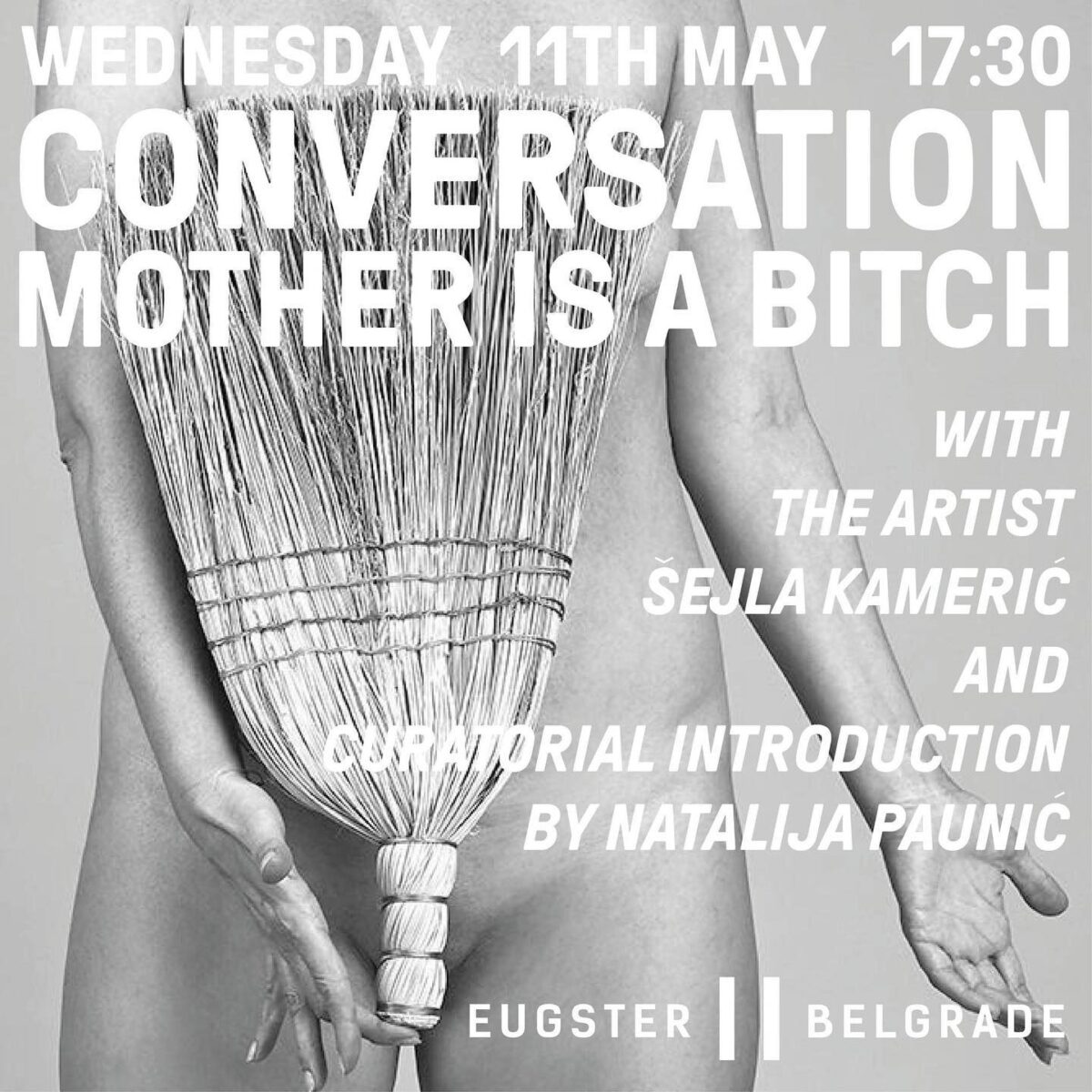

Conversation with Šejla Kamerić | Mother is a Bitch

- Inquire about the artist

- Back to artists

Thinking about the exhibition text – Mother is a Bitch

Natalija Paunić

Sometimes it feels as if the text needs to contain certain words, structure and references in order to pass as a legitimate exhibition text, even if written in a way that’s seductive and unconventional. This is not to say that I’ve not fallen into that same trap; I, too, frequently mention post-structuralism, juxtaposition, the Anthropocene, and similar platitudes, even though I wasn’t pronouncing one of these words correctly in Serbian, which I found out later in a formal conversation about it. Should I be ashamed of this, or is it only easy for me to admit it because, as a former professor of mine said: women are allowed to be clumsy, silly and whimsical in academic circles. They’re not taken seriously anyway.

There’s that word – seriousness. Exhibition texts need to be serious in order to be taken, well, seriously. But who said that?

The professor I mentioned was teaching women’s writing as part of her class. She introduced me, a few years back, to Helene Cixous’s Laugh of the Medusa. My main take was, not only that it’s impossible to communicate everything we want using our common language designed to serve a particular system (the patriarchy, as I mentioned in the text for “Burn by Staying Cool”), but also that, in order to communicate anything at all, as Women (and this also potentially stands for anything that’s not Men, so even men, lowercase m), we should find a different way to write. My first reaction was: the feminine is in between all the lines, right? In the spaces, on empty pages, because it’s inexpressible; but this is too simple an approach and very unassertive as well. Sometimes, I go back to Maggie Nelson’s indecision in The Argonauts as to whether words are, or are not, good enough. I actually don’t know, but I am questioning whether the institutional. curatorial, political or corporate leaderships that take themselves too seriously with words and formalities have brought us to the stubborn place of little hope for any change, where we are today.

Šejla Kamerić’s solo exhibition at Eugster || Belgrade, Mother Is a Bitch, opened without an exhibition text and instead with the beginning of an interview between herself and the curator Adriana Tranca. This was a choice, and so was the self-portrait as a medium, the works’ positions in the gallery space and the ongoing approach to the accompanying materials.

The exhibition shows three series of new photographs, which Šejla underlines are self-portraits, and there is one knitted object added, hiding at the gallery entrance (this is also the gallery exit – a material symbol of things coming together in time). The self-portrait is one way to reclaim what has been taken away from a person, as it offers the possibility to show our own body the way we want it to be shown, on our own terms. This possibility is particularly important for women. Šejla has been approaching this subject, from various angles and for many years through works such as Basics (2001), Bosnian Girl (2003), 30 Years After (2006), June in June Everywhere (2013), Embarazada (2015), Unknown (2018), to name a few. In a sense, she works with self-image even through the constructed ready-made portraits of other people, real or representative: The Saponified Jacket of Melania Trump (2020), or for example We Come with a Bow (2019), through which the work impersonates the experience of the individual regarded, or women as a group and their shared identity as an inevitability in this society.

The new series are grouped as triptychs in three forms: figures, portraits and torsos. Figures show Šejla assuming roles in relation to different spectrums of public life: art/entertainment, labor/military and religion/sacrifice, using her body and different types of brooms to illustrate each position. As opposed to the thick sense of corporeality coming from these works, Portraits show something much more ethereal, with Figures reflected in the glass that is now part of the frames. Portraits are made with double-exposure, which effectuates the hold of Šejla’s facial expression. Implicitly, they recreate the wonder as to how a face, or just a gaze on its own, has the power to elicit such precise feelings in the spectator (shame, guilt, pain, compassion, fear), a reaction caused by many of her previous self-portraits.

The works from the Torso serie present as vaguely sexual, however the eroticism seems to be literally and intentionally “blown out of proportion” because of the prints’ size: they are massive, slightly tilted toward the audience, coming at you from the corners of the space. The head is cut off to further underline the size of the bodies and to keep the focus on the body itself, and not the persona that walks it. The photographs show a woman with a broom between her legs, only this time, the purpose of the broom is not mystified by the accusations of anything “unearthly”. There is nothing supernatural about a woman masturbating (or is there?). The idea is, of course, to tackle the age-old trope of the witch, a single, sometimes old, usually childless woman, who does “strange things” with a broom (a household object available to her) between her legs. But the connotation is far beyond the sexual. As Emily Wardill says, in To Inhabit a Witch: “In the ongoing derision of female lives, we are often relegated to witches, bitches, and whores, with the implication that we may perform merely transactional roles, rather than transformational ones. As we remain stuck in-between an artistic dimension and a political dimension, we necessarily keep an ear to the ground for how we might learn from one another, so that our work might effect political change. Meanwhile, our actions are characterized as cunning, and our ability to bring forth the changes we intend is attributed to the supernatural”. In other words, what was perceived to be unnatural, or rather unwanted (a woman leading the way, for example, or as Wardill says, making a change) transformed into the folk-tale of the supernatural, a myth, a scary story about the scorned, ugly, unwanted witches. This is abuse by proxy; and this is why we need to learn from one another.

To give time for the exhibition text to gestate means to reclaim some silence, as silence has always been our language; to embrace a slower pace, patience, weaving, as Edi Muka noted in The voice of shuttle revisited – his quote will be included in the texts accompanying this one. To allow for thoughts and time to help one another.

What’s so scary about a woman patiently waiting (weaving, knitting – another hint at the hidden object, the “Hooked” piece in the show)? This is a question I asked myself many times recently, having thought about horror shows with leading female villains and monsters, about women stuck, imprisoned in towers – both literal and symbolic. I asked myself then, if it’s the obsessive adoration that these women have (for their lovers, children, fathers etc.) that is scary, or if it’s the patriarchy itself that needs to invent these characters in order to explain everyone’s growing fear of the rules that it persistently imposes (the imperative to have a family, for example; to be a proper part of the society; to insist on one’s own political identity; to choose a role, to take a side).

Even if I am definitely not asking any new questions (unfortunately, because this means that our society has regressed substantially in the past decade or two), I, or rather we, would like to cherish the non-canonical text, because it’s the least we can do, for now. We’d like to have the exhibition text, catalog, develop over time and become part of a bigger research, independent even from the exhibition itself – even if clearly inspired by it and made on its occasion. Because what kind of art practitioners would we be, if we didn’t leave space for our projects to grow and give impetus to new ones, to learn from each other; if we insisted on them being finished from the start?