Exhibition

To speak of a dead nation in the language of lust

Text by Natalija Paunić

There are two instincts in life: one that promotes pleasure and harmony through libido, the other based on self-destruction and destruction in general. Freud aptly named them Eros and Thanatos, instincts of life and death (Beyond the Pleasure Principle, 1920). To explain Thanatos, Freud often used the example of war veterans who tended to relive their traumatic experiences in dreams or even consciously, concluding that living beings, in fact, have an urge to die. This desire gets perpetually contested by the will to live, but experience tells us that, as far as individual human life is concerned, Thanatos always wins.

In a way, this makes Eros the underdog, so Eros needs to develop unusual tactics to confuse the opponent, to see eye to eye with Thanatos, maybe even to become one.

Saša Tkačenko portrays these relations almost unintentionally, through a body of work operating in an invented temporal context takenaway from the actual course of history. Stemming from particular social understandings and political phenomena, the motives in his art bring the timeless to the contemporary. This is achieved through concrete references to everyday life and popular culture, quotes, objects and symbols that have a specific meaning for each of us, juxtaposed with an abstract emotion that dances the line between the two extremes, love and death.

The silhouette between the light and darkness becomes most tangible in Tkačenko’s works portraying violence, hooligans, vandals and their props. Behind the univocal depiction of what is undoubtedly dark, such as an urge to smash someone’s skull (Skulls Will Be Crushed, 2011), lies an entireworld of passion. Right alongside an impulse to destroy, there is a yearning to belong – to a particular hooligan group, to a pack or just the world as it is in this moment. At times, this inner battle comes out in form of a dialogue, like in the announcement text for Ruins of Future Utopia, a quote from Trainspotting 2 where two characters discuss going home and leaving the past behind in moments before they do so

Well, I’m trying hard (…) but I’m not feeling anything. We were young. Bad things happened. It’s over. Can we go home now?

Two hours to the next train.

Oh, for fuck’s sake.

Look, we’re here as an act of memorial.

Nostalgia. That’s why you’re here. You’re a tourist in your own youth.

Proposing a similar dialog, Ruins of Future Utopia meditates on the frozen moment of a fiction that is former Yugoslavia, the idea of whichis malleable, unstable and entirely depending on the narrator. Even Tkačenko’s personal experience with the subject is a combination of modifiedmemory and of what others have had to say, as the narrative becomes closer to fantasy than history over the years. Yugoslavia never gave it to us,to generations that were young enough to remember the 90’s for its ‘good parts’, playing with friends outside, homeschooled, or having the best of

times because the world might end tomorrow anyway. The third-way promise was made, broken and never mentioned again, so most of us agreedto a toxic relationship with the past. A little bit like the veterans from Freud’s research, our generations, as well as Tkačenko’s series of work, seeYugoslavia through the prism of unrequited love.

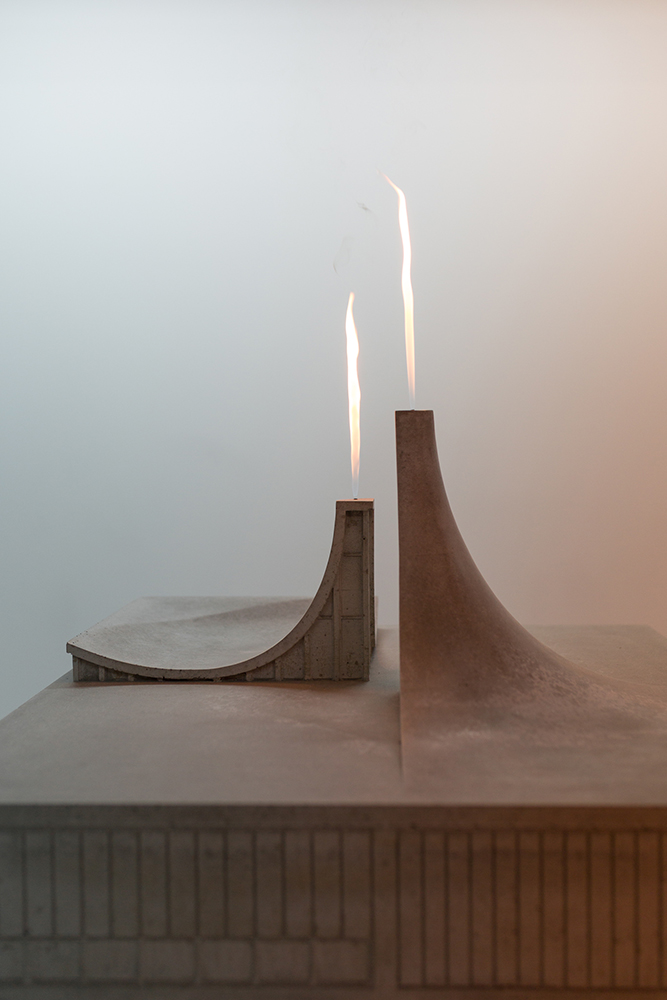

The exhibition space presents elements suspiciously filed under the category of ruins. Carried out with fastidious precision, freshly taken out of an art foundry, they are called ruins but there’s hardly anything broken at their surface. These are ruins of an ideology rather than ofcommunist monuments; they do not resemble debris, but they do provide enough material to provoke memory and yet to never become real, which is exactly how nostalgia operates. The goal is to keep you clinging to it – and surprisingly enough, you do, because searching for the original feeling gives a new kind of sublime pleasure. Nostalgia does this, like a substance, a drug, an agent of seduction, a lover who cannot love you back but never really tells you no. It switches between roles, soothing and tempting like Eros, dark and deadly like Thanatos. As you let the past into the present, the present gets wasted away.

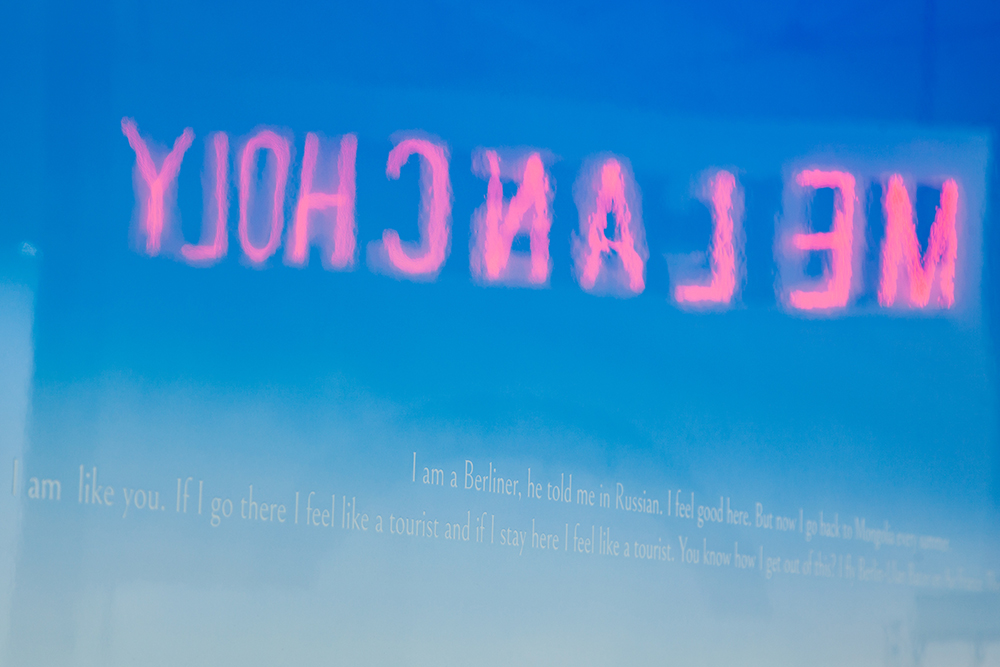

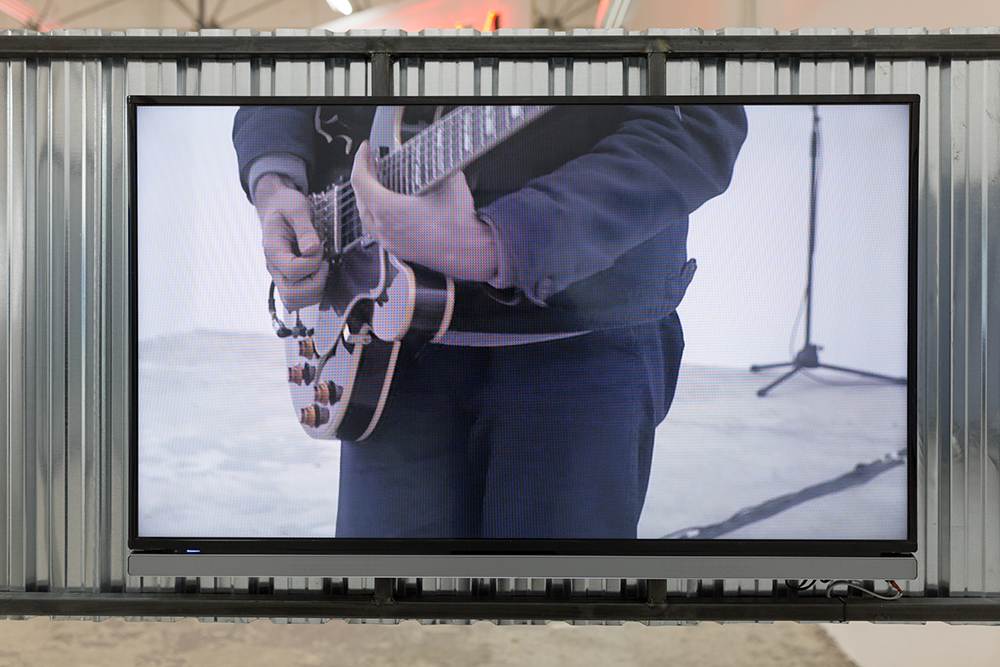

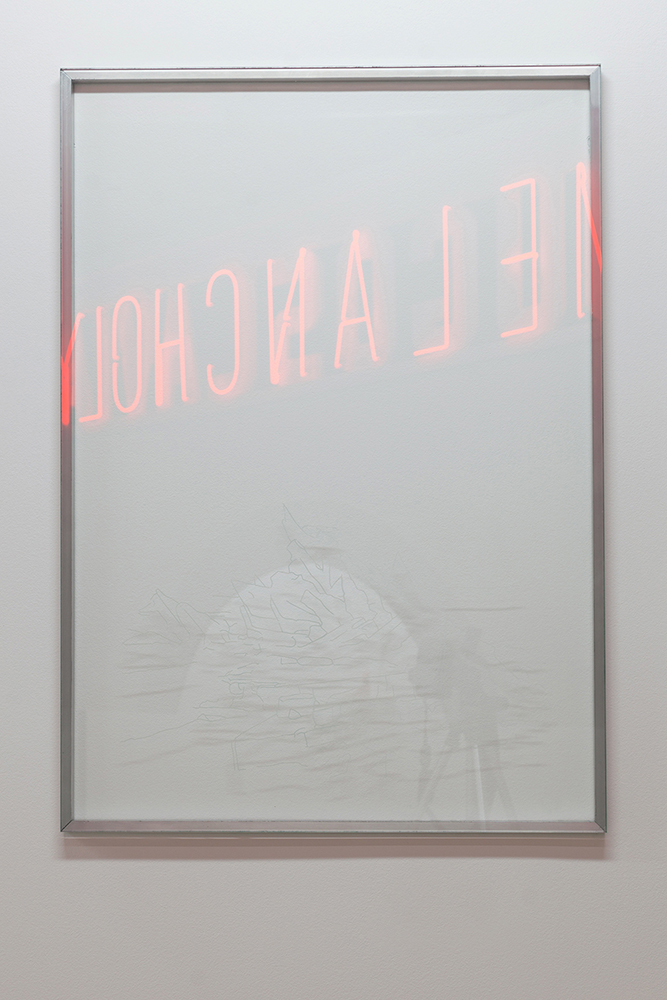

Springing from this ambivalence, two primary colours fight for dominance in the space that hosts Ruins of Future Utopia. Red neon light helps write out the word Melancholy in one of the artworks. In the other corner of the room, an image of a clear blue sky bears its blurryreflection: a little bit of red in the blue, a bit of fire in your sadness; and yes, there’s also an actual open flame on display. Between what is being told, what these installations represent and what they look like, stripped of meaning, there is a giant schism. Tkačenko tells the story of his fleetingpast, a story most of us can relate, if not to our war-torn countries, then to those who failed us or to our own disappointments. But while at it, he gives us bottles of champagne, flames resembling candle light, red neon, even music. Perhaps the most erotic moment strikes when in front of analmost empty sheet of transparent glass. At its bottom, there is an engraving of The Sea of Ice originally painted by the German romanticist Caspar Friedrich David. Also known as The Wreck of Hope, the painting symbolised the darkly beautiful reality through shards of ice hiding a sunken ship. In Tkačenko’s interpretation, we don’t see the ship at all and the icy surface is reduced to a countable number of lines. There it is, concealedimage of a catastrophe, hidden in plain sight on glass cold as ice, right opposite from a gas tank providing the exhibition with fire, literally and metaphorically.

It seems that Tkačenko is undecided whether this daydream brings him pleasure or pain. In relation to the agency of colours, his works act as if we should not even try to choose between the blue and the red pill (and while at the Matrix reference, the movie’s release date coincidedwith NATO bombing of Belgrade, which, for most of us, killed all the remaining concepts of any Yugoslavia). Red and blue are like passion and detachment trying to balance each other out. In the true moment of nostalgia, they exist together. They even exist in our (both Yugoslavian and Serbian) national flag. Perhaps the moment of ecstasy is really the one just before pleasure turns into pain, before the ship collides with the iceberg, before, in our memory, we meet with disappointment and have a chance to remember the utopia once again, and again, and again.Or maybe it’s the other way around. Maybe the ruin is more attractive than utopia, because it’s a little bit wrecked, a little bit hopeless, impossible to save, a damsel in distress, an eternally seductive, fucked-up paramour. And because we want to fix it, we keep on going back to it. On Freud’saccount.