Exhibition

THE NOTEBOOK

06 June – 05 September 2020

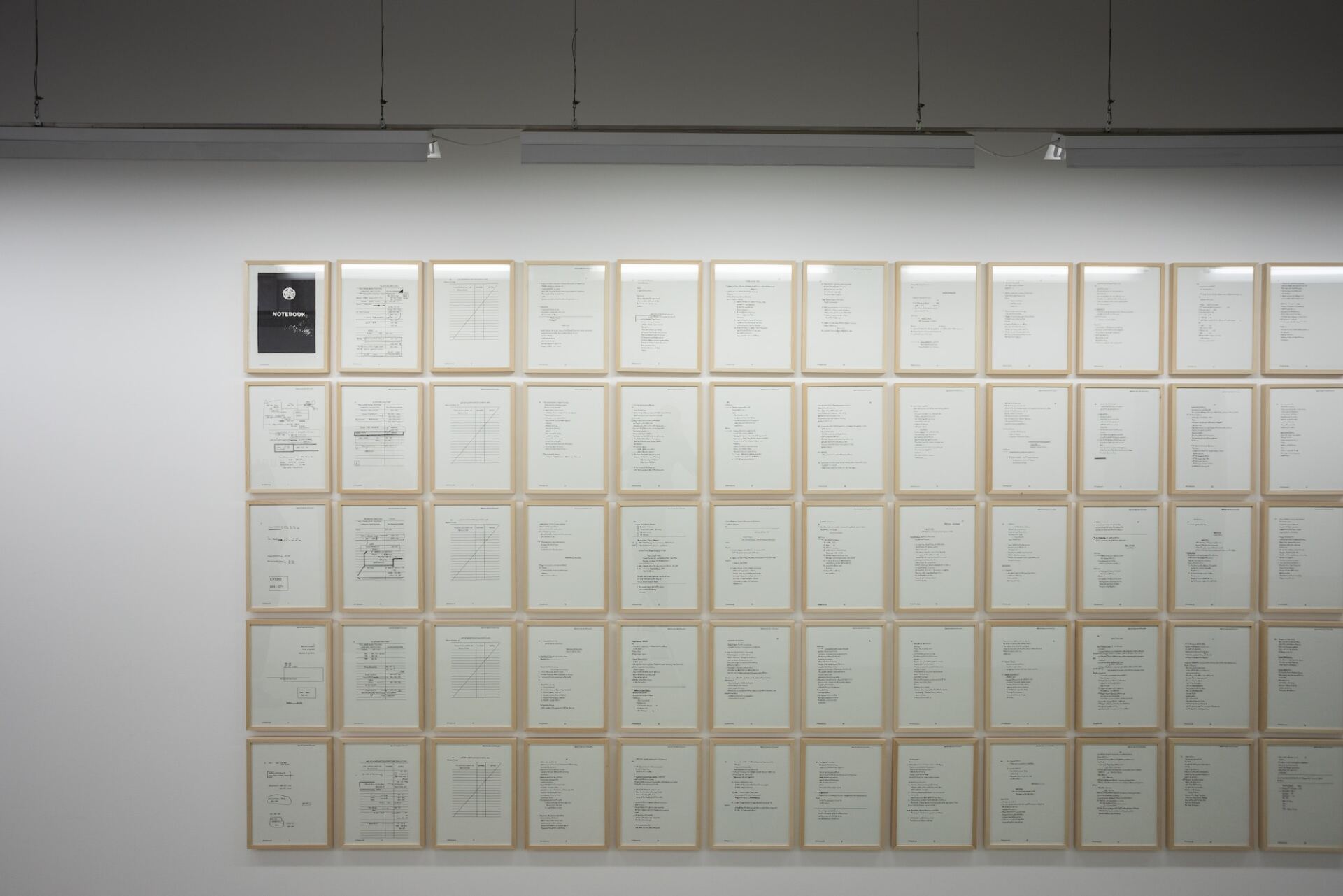

“The Notebook” is a work based on Ratko Mladić’s war diary – a document that was used as evidence in his trial before the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) in The Hague.

Miladinović has been working on this monumental project for several years. It consists of a series of carefully drawn pages of Mladić’s diary that were prepared for the ICTY trial. The background of the diary is a story in itself. The diary was found in 2010 in Belgrade during a search conducted by the ICTY investigation team. Missed in previous searches, this time a fake wall was found in one of the houses where Mladić was hiding. There, behind the wall, the team made the incredible discovery of a large number of his personal diaries that had kept during the war in the 1990s as well numerous audio and video cassettes, photographs and documents testifying to the war actions.

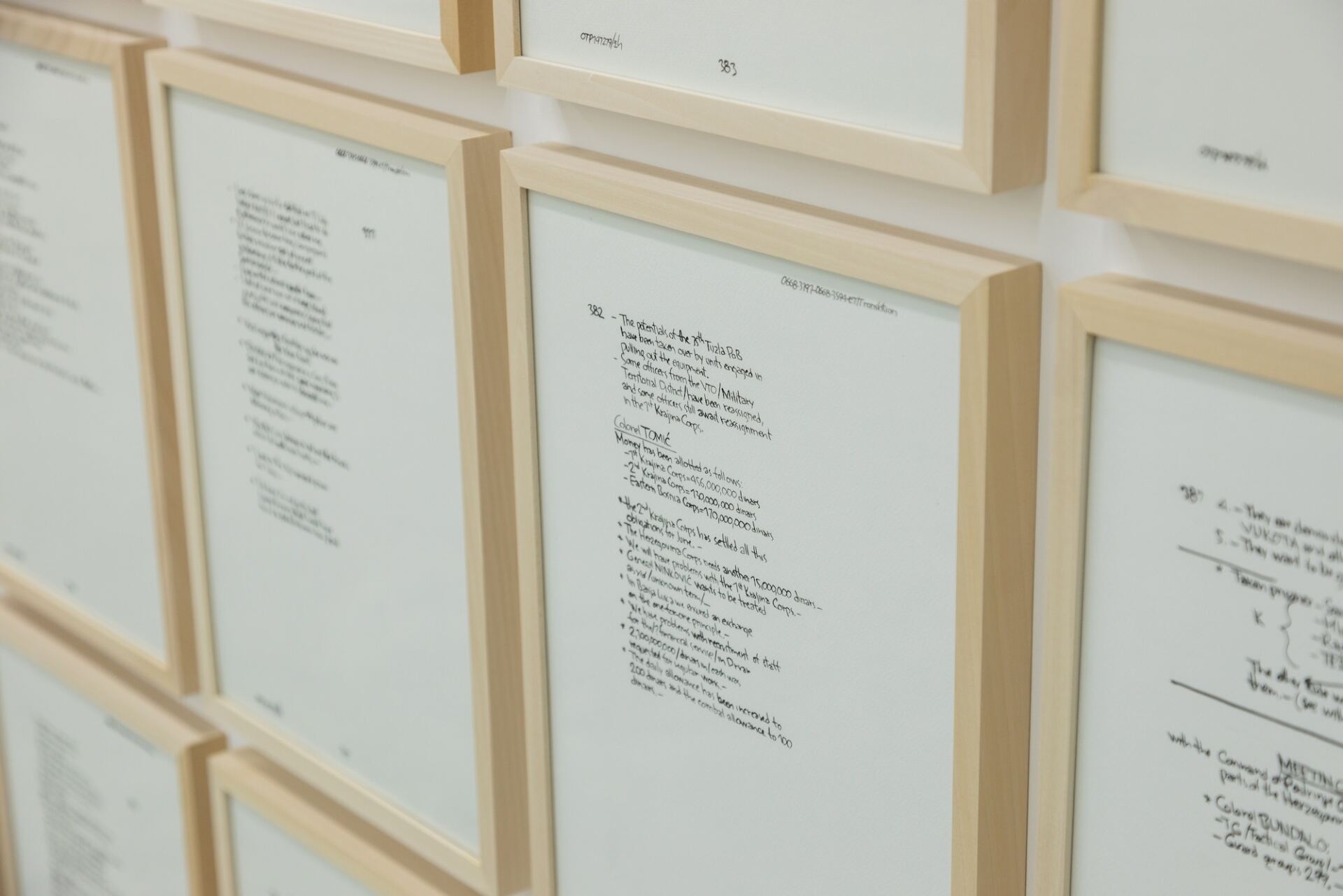

After this notebook was found by the ICTY team, they had to carefully prepare it so it could serve as relevant evidence which would hold up in court. First, the ICTY hired a team of graphologists, expert witnesses whose task it was to translate the Mladić’s writing. Their task was to use their authority to stand behind the translation and verify that the text really is by the hand of Mladić. Every letter, every line, had to be carefully converted into a computer text that would be readable by the bureaucratic audience of the court. Then the court had to translate the material into English for it to be offered as evidence and to satisfy the need of international composition of the court panel. If they didn’t do all of this, the diary would not be able to be used as evidence.

In “The Notebook” Miladinović uses this court document and has carefully drawn each letter by hand, page by page of all four hundred pages of the diary. This process raises a number of questions. What makes certain material adequate for a legal bureaucratic forum? What is the role of an expert witness in that process? What is the role of artistic imagination in the processes of dealing with the traumatic past? What are the limits of archives and archival material that has already served its purpose in the court? What kind of afterlife or potentiality does this material have?

For many years, artist Vladimir Miladinović has been following a daily routine devoted to archival research of historical periods where it’s difficult create a narrative to reach broader social consensus. By transferring the collected material into the form of a drawing, faithfully redrawing the collected material in the ink-wash technique, the artist creates a series of works through which he tries to create a personal relationship with the material.

Miladinović is an accomplished artist who has received numerous accolades for his work. He won the award of the 53rd October Salon, as well as the main award of the fund for drawing “Vladimir Veličković”.

The exhibition is supported by the Belgrade forumZFD and will be open until the end of July 2020.

–

Segments from the text for the catalogue:

Aesthetic Contestation and the Archive: Vladimir Miladinović’s The Mladić Diaries

Dr. Henry Redwood – King`s College London

[…] In drawing inspiration from the Mladic Diaries from the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia’s archive, Vladimir not only challenges the logic of the ICTY’s archive, but the archival drive more generally as he opens the archive to new encounters and new imaginative possibilities. This is made possible, as the following suggests, through the aesthetic politics located in Vladimir’s practice.

This practice revolves around this question of archival power. His work meticulously reproduces the archival records of silenced or contested aspects of the former Yugoslavia’s past in ink wash. This draws attention to the logics and drivers that led to the exclusion of these records from popular imagination – frequently linked to the systems and processes that contributed to the occurrence of violence in the first place, such as nationalism and the shift from socialist to capitalist economies. In resituating these records, Vladimir alters boundaries of ‘the limits’ in the present, or, following Ranciere, disrupts the ‘disruption of the sensible’ which renders certain knowledges ‘common sense’ whilst other are made illegitimate. His work has drawn on numerous archives, including newspaper archives and museums archives, and within these his practice has focused on numerous different types of documents, such as lists, maps, posters, pamphlets and photographs. However, a reoccurring archive in Vladimir’s work, and which underpins The Notebook, is the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY)’s archive.

[…] Whilst this approach defines much of Vladimir’s work, this is equally key to The Notebook. This renders the process through which evidence is produced in the courtroom visible, and also turns the logic of this process against itself. In re-drawing by hand each page of the notebook, Vladimir returns the evidence to its original state – as a hand written and personal object. But in the reproduction, the gap between the personal reproduction, – gesturing towards the notebooks original form – jars against the attempts to tame the pages of this as evidence which remain visible within the digitised reproduction (then reproduced by Vladimir). The oddly neat circles, the double underlined passages, all of which evidence the courts concern with objectivity, authenticity and accuracy, are all reproduced in Vladimir’s work in a manner that puts a mirror up to that process to show it for its peculiarity. But in putting these aspects of the diary front and centre of the work, it shows the limits of the court’s that mode of knowledge production and ultimately, its inability to tame the memory of violence. This is perhaps made particularly stark in those moments when the digitised version reads ‘indecipherable’. More than this, the work – which occupies a 50 square meters wall – overwhelms the viewer in a way that also gestures towards the difficult nature of processing and dealing with the past.