News

ŠEJLA KAMERIĆ – FIRSTBORN

- Back to news

Focusing on questioning identity values based on personal experience, as well as societal patterns that involve stereotyped notions of women and femininity, the exhibition Firstborn embodies the artistic perceptions of Šejla Kamerić, which are rooted in pronounced empathy, as a key mechanism of communication in her artistic work. The exhibition was created in a kind of conceptual collaboration with the curator Milica Bezmarević. At the exhibition, for the first time, the work done for MSUCG will be presented, which in its content refers to the mentioned topics, pointing to the issues of retrograde perception of gender heritage.

Here you can read a conversation between Šejla Kamerić and curator Milica Bezmarević on the occasion of the artist’s exhibition Firstborn at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Montenegro, published in the monograph Mother is a Bitch by Šejla Kamerić.

ŠK The only thing that is certain is uncertainty itself. In this region where we were born and in our native language, the word insecurity is very often used instead of the word uncertainty. This overlapping usage indicates that the only thing that is certain is the lack of any security. In the state of absolute uncertainty, security is claimed through categories such as gender, but also place of birth, language, nation, skin color, or class. However, when they’re faced with reality, these categories only guarantee us even more uncertainty. Does insecurity bring us together? Do the connections we make, which transcend these categories, guarantee safety?

MB While I’m trying to write an answer to some of your questions, things are happening, right here, around us, in the spaces that surround us, in the space where we are born, which emphasize that exact feeling of insecurity and uncertainty that you’re talking about to the extent that it makes you feel short of breath. Yes, it seems to me that insecurity does connect us, or rather that facing insecurity makes us want to connect with others, individuals or communities who identify with similar experiences. On the other hand, I don’t believe that it is actually possible to achieve the desired feeling of security in such relationships, precisely because of their setup, in which we expect understanding, togetherness, unity… Is the security we are talking about defined within the scope of some kind of convention? Social or individual conventions which, again, I don’t believe can guarantee any true solidarity.

When I talk about solidarity, I instinctively think of solidarity among women. Is the category of sisterhood already largely obsolete?

There is a decades old myth in Montenegro about the inviolable value of the male descendant in the family who should inherit everything and continue the family line. This retrograde narrative of a backward part of society still lives on today and Montenegro is leading the negative statistics of forced sex-selective abortions of female foetuses. It is precisely women, future mothers, who indisputably agree to such an act because of their understanding of their duties towards family, community, tradition, etc. I cannot even imagine how terribly insecure and uncertain those women must feel deep inside while expecting the gender revelation of the child they are carrying, on which its future life depends.

While we were preparing for your exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Montenegro in Podgorica, we talked about this for a long time, and suddenly a space opened up, in which everything clicked and connected, your previous works, huge crocheted nets from Hooked (2010-) and curtains from Rose Garden (2022), nudes from the series Mother Is a Birch (2022)… The exhibition Firstborn arose from that exact context, from the question of the woman in the Western Balkan region, but in fact everywhere else as well. Lars von Trier’s movie Breaking the Waves (1996) comes to mind – I cannot think of a more powerful story about a woman’s sacrifice for the sake of someone’s salvation, but through sin. How do you perceive sacrifice? As women, are we destined to sacrifice ourselves for the family, community, and society, or are these imposed frameworks of social conventions that we all carry as part of our gender heritage?

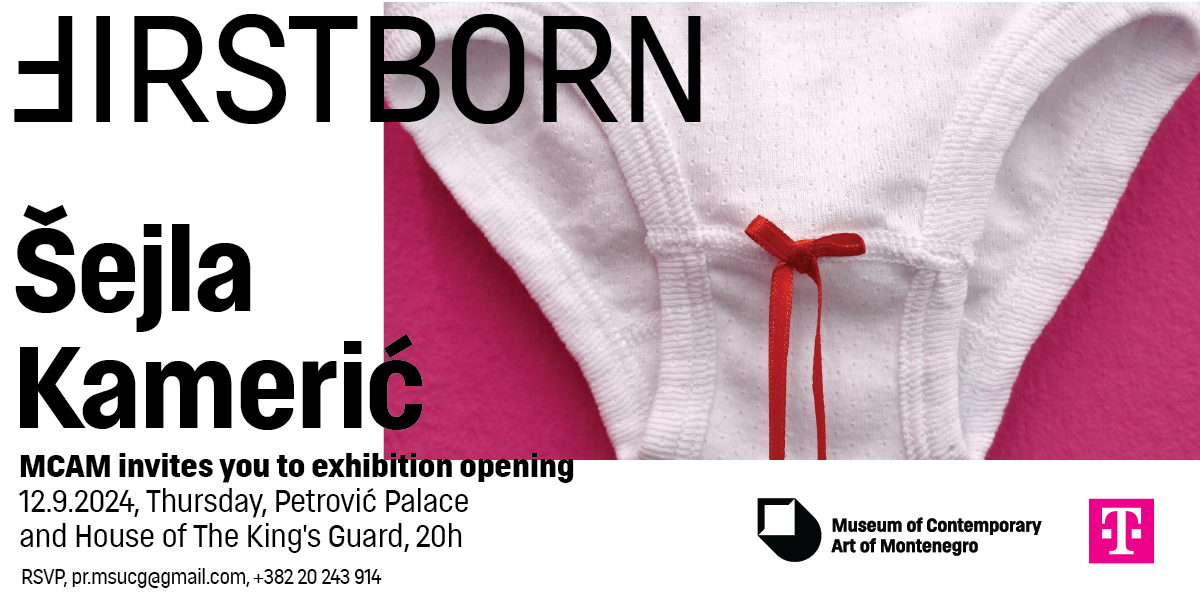

ŠK We are forced but also taught to both bow down and give ourselves as a gift. To be given away as a gift. It is the predestination we deal with and fight against. My work We Come with a Bow (2019) can maybe answer that question. For the exhibition in Podgorica, it is conceived as an installation that exceeds the gallery space. Red ribbons of the bows come down from the wall, spread across the floor and intertwine, coloring the entire space in red. Finally, the ribbons come out of the windows and flutter in the park in front of the gallery. It is a big installation arising from a small bow on children’s panties for girls. In such a setting, the individual experience is placed in the context of social conventions and policies imposed upon women. Bleeding is predestined. But what is the burden of that predestination and how heavy is it? Gender is an identity with which we come in this world; it is not necessarily comfortable nor easily accepted or changed. Building an identity often means accepting the imposed. Consciously or unconsciously, women accept the imposed victim role as something predetermined. In order to deal with it, we must first recognize that this is an imposed role and foremost deal with ourselves and our relationship to our own mothers.

The role of the woman as a victim is most often learned and passed down the female line as inherited “knowledge.” The work I created for the exhibition Firstborn titled My Mother Calls Me Son, Not Sun (2023) thematizes the complex relationship between mother and daughter. What is expected from a daughter? What is the ideal of the sacrifice that is imposed on her? Is it complete surrender and all that is associated with sacrifice … renunciation, deprivation, bloodshed, giving. offering, suffering, giving birth, being exploited, subjugated, humiliated, prostituted, crucified, exorcized? In the end, the daughter is called Son as a sign of affection. It is a reward and proof of an unattainable, high position. A SON is the SUN, he is the center, a daughter is a daughter, she only serves and will never be neither a son nor the sun. She will give birth but will not extend the family line, she will do care work but will not be the protector, she will sacrifice herself but will not be the hero. Her sacrifice cannot be rewarded, there is nothing sublime in it. It is not the kind of heroism that is rewarded. In the installation My Mother Calls Me Son, Not Sun, these connections are materialized through balloons on thin silk threads tied to a stone, in which the word “SUN” is engraved. During the exhibition, the balloons will deflate and fall to the ground, but remain tied by golden threads to the stone that stands still. When we talk about victims, we always talk about perpetrators as well. The question of responsibility and guilt is unavoidable, because rejecting the role of the victim does not erase the crime, it does not wash away the guilt, it does not grant amnesty to the perpetrators.

MB Your work Bosnian Girl (2003) is undoubtedly an iconic image of the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the entire horror that happened on the grounds of the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s. For the first time after so many years since the genocide in Srebrenica, that piece will be shown in Podgorica, and I believe that is extremely imponant. Because as you said, when we talk about victims, we always talk about perpetrators as well. For all of us as individuals, facing such things can be a painful and tiring process, but without it, there is no healing, no recovery. For all of us as a community, the questions of responsibility. acceptance of guilt, understanding and compassion for the victims are equally important. Bosnian Girl is a kind of art piece that artificially articulates entire layers of the deepest impressions, experiences and traumas, the overwhelming burden of war suffering that goes beyond your personal memories. I’m writing these lines under the impression of what you told me, and it’s something you very rarely talk about in public. During the war, you were sexually assaulted by a UN officer, you were pushed against a wall, but you managed to detend yourself and run away. In another situation, you had to jump out of a moving car in which you were abducted to be raped and probably killed. I understand your silence during all these years, as it is such an intimate and extremely personal experience. Nevertheless, I wonder, did you, even as a victim, have some kind of prejudice? Did you think it wasn’t worth talking about because some other women actually ended up being raped, kidnapped and killed?

ŠK That is exactly why I didn’t talk about my experience. But I also didn’t keep silent, my works are my testimonies. In them I talk about mysell, but not only about myself but about the collective and shared trauma. There is nothing special in violence and prejudice. We are all victims, and we can all be perpetrators. We have the same feelings, we are all in this together. We create this cruel world. The real questions are: What do we learn from violence? Can humans change? And be less cruel? Can we manage to not repeat the same mistakes? What kind of society do we want to build? The title of the exhibition that we conceived is Firstborn. You spoke about the context of birth in Montenegro and how deeply we are imprisoned in the patriarchal past. The title of the exhibition refers to that, but it can also be seen as a desire to start over – to be born again, to be born as first ever. To be born tirst, born as women and to start life without trauma and pain. Firstborn, smarter, nobler, better.